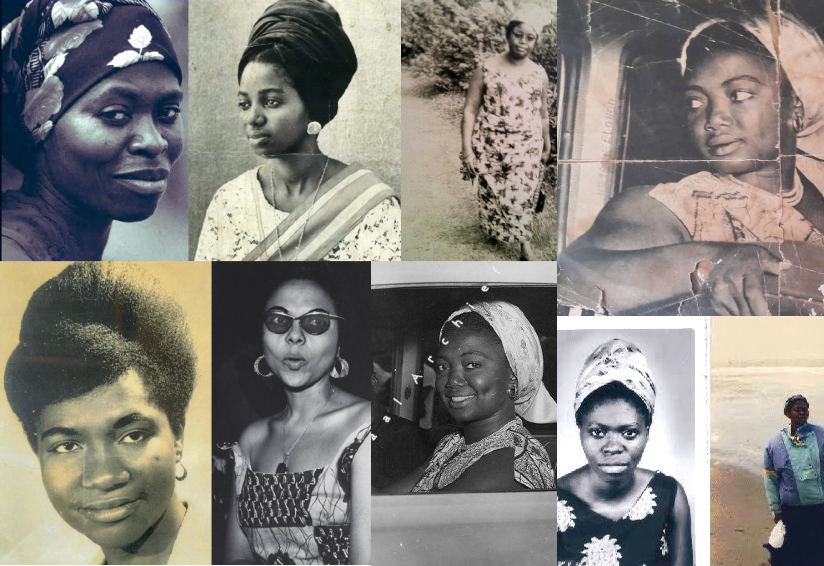

Too often pushed to the margins of official narratives, bold Congolese women played a crucial role in the struggle for the independence of the Democratic Republic of Congo, proclaimed on June 30, 1960. As pioneers, they took part in nationalist movements,sometimes on the front lines, sometimes behind the scenes, but always with unwavering determination.

After independence, as the country wavered under the weight of crises (the Muleliste rebellion, the Katanga secession, political instability), these women remained active. Their voices resonated in political, social, and community spheres. With courage, they worked tirelessly for reconciliation and peace, weaving networks of solidarity, initiating dialogue, and laying the foundations for a more stable future.

Long overlooked by mainstream historical accounts, these female leaders now deserve recognition for their invaluable contributions. Here are a few of these key figures,actors in the shadows but architects of Congolese history.

Marie José Sombo, “a black Eve “

Born in 1945, Marie-José Sombo took her first steps into the media world at a time when women’s voices were still stifled in the Congolese public sphere. At just 16 years old, she became an announcer at Radio Léopoldville, a remarkable achievement for such a young woman, and a first for a Black Congolese woman in a field still largely dominated by men and colonial powers.

A few years later, she joined the editorial team of the newspaper L’Avenir, where she stood out as the only Black female journalist of her time. In the pages of this influential paper, which published a weekly supplement titled Actualités africaines every Thursday, Marie-José Sombo worked alongside major figures of Congolese journalism such as Jean-Jacques Kande, Antoine-Roger Bolamba, Gabriel Makoso, Philippe Kanza, and André Genge.

What truly made her a pioneer were her feminist columns, bold and visionary. Long before women’s issues entered political debates in Congo, she denounced the invisibility of Congolese women in decision-making spheres.

In April-May 1956, while a delegation of 16 Congolese, including Patrice Lumumba, was in Brussels for a political visit, Marie-José Sombo expressed outrage in her writings: no Black women had been invited to be part of the trip. “How can it be explained,” she asked, “that not one Black Eve was invited to be part of this delegation of visitors?”

With this statement, she broke a taboo. She reminded everyone that women also had a role to play in nation-building, not as mere companions, but as full actors in history.

Maria N’koi: The Unyielding Healer Who Defied the Empire

Long before independence, while Congo was still under Belgian colonial rule, one woman made history through her bravery and resistance. In 1915, in the country’s west, Maria N’koi, a charismatic and feared healer, led an insurrection against the colonial order.

A mystical and inspiring figure, she openly opposed injustices imposed by the authorities: exorbitant taxes, forced labor, abusive requisitions… Legend says Maria N’koi, whose name evokes the leopard, a symbol of strength and cunning, was surrounded by these wild cats, embodying an untamable power. She healed with traditional remedies, but her “prescriptions” went far beyond medicine: she called for revolt and denounced the colonizers as the true cause of the Congolese people’s suffering.

During the turmoil of World War I, she even prophesied the Belgians’ defeat by the Germans, a subversive message that galvanized the masses. Her words ignited spirits, and her gatherings attracted growing crowds. To the colonial authorities, she became too great a threat.

Maria N’koi was eventually arrested and deported by the colonial authorities. Yet her fight, rooted in a spiritual, political, and social vision, remains a powerful symbol of Congolese female resistance. In the history of anti-colonial struggles, she was among the first to wield speech as a weapon and healing as a form of liberation.

Léonie Abo: Midwife of the People and Shadow Fighter

Born in 1945 in Malungu, Kwilu province, Wassis Hortense Léonis Abo (better known as Léonie Abo) grew up under colonial rule during profound social upheavals. Orphaned at birth after her mother died giving birth to her, she was given the name “Abo,” meaning “mourning” in the Babumda language, a heavy word that would accompany her life.

At just 14 years old, in 1959, she was torn from her adolescence by a forced marriage to Gaspar Mumputu, a violent man. In this domestic hell, she found an escape: political engagement. That same year, the African Solidarity Party (PSA) was founded, and Léonie, still a teenager, was captivated by its anti-colonial ideas and fight for Congo’s independence.

Before becoming a rebel figure, Léonie trained as a midwife and pediatric nurse at Foreami (Queen Elizabeth Fund for Medical Assistance to the Natives), overseen by the Belgian queen herself. In 1957, she was part of the first cohort of this initiative aimed at healing Congolese people.

In 1963, her life changed drastically. Kidnapped by rebels for her medical skills, she was taken to the bush where she met another resistant leader: Pierre Mulele, former Lumumba minister and leader of the Mulelist rebellion. A love story blossomed amid war. But Léonie was not merely the insurgent leader’s partner, she became a key player in the struggle.

In the bush, she cared for the wounded, led troops, and fought. As head of the rebel forces’ health service and rearguard commander, she embodied the alliance of care and armed resistance. A woman with a rifle, a midwife turned fighter. A survivor.

After Pierre Mulele’s brutal assassination in 1968 in Kinshasa, she was imprisoned by Mobutu’s regime. Released a year later, she exiled herself to Congo-Brazzaville, where she lived until the dictatorship fell in 1997.

Now 78, Léonie Abo continues to share living memory of this troubled era. In the documentary film Abo, a Woman from Congo by director Mamadou Djim Kola, she delivers a moving and precious testimony about colonization, rebellion, and women’s roles in armed struggles.

Léonie Abo is more than a historical name, she is the living memory of a Congo in turmoil, a woman standing tall through the storm.

Joséphine Siongo Nkumu : A Woman’s Voice in the Colonial City

During the final years of Belgian colonization, as Congolese voices began timidly to emerge politically, one woman stood out for her courage and determination: Joséphine Siongo.

In 1956, she made history as the first Congolese woman to sit on the Leopoldville city council, present-day Kinshasa. At a time when political institutions were largely male-dominated and controlled by colonial authorities, her presence marked a powerful symbolic break: a Black Congolese woman taking part in city affairs.

Her commitment did not stop there. In 1957, she was appointed Congolese delegate to the World Union of Catholic Women’s Organizations. This nomination made her the voice of Congolese women on the international stage, carrying the concerns of women in a country still under tutelage but socially and politically stirring.

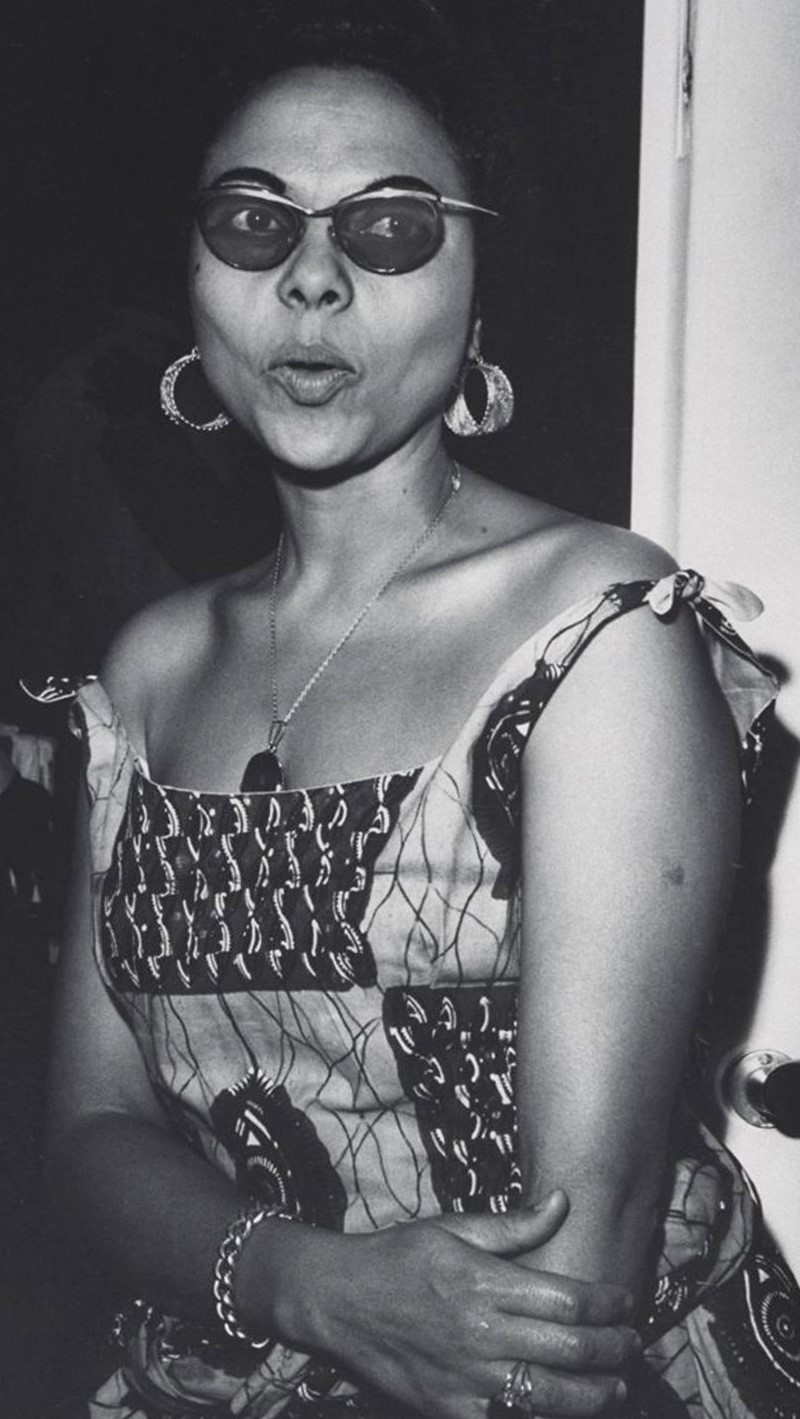

Andrée Blouin: The Black Pasionaria of African Independence

A great orator, political strategist, and tireless pan-African militant, Andrée Blouin was one of the most powerful and bold voices in Francophone Africa’s anti-colonial struggles. A woman of fire, who crossed borders and barricades to amplify those whom history sought to silence.

Born December 16, 1921, in Bessou village, Central African Republic, she was named Andrée Madeleine Gerbillat at birth. Daughter of Joséphine Wouassimba, a young Banziri woman, and Pierre Gerbillat, a French merchant, she came from a union shaped by the unequal relations of colonial society. As a mixed-race child in a segregated world, she faced humiliation and marginalization early on, a formative experience fueling her revolt against racial discrimination.

In the 1950s, her anger turned into action. She engaged actively in Guinea alongside Sékou Touré and helped mobilize for the country’s independence in 1958. Soon after, she moved to the former Belgian Congo, joining the African Solidarity Party (PSA) led by Antoine Gizenga. There, too, she quickly made her voice heard.

On April 8, 1960, weeks before Congo’s independence, she founded the Movement for African Women’s Solidarity, dedicated to mobilizing women in the anti-colonial struggle. She toured cities, energized crowds, and delivered fiery speeches. Thanks to her zeal and energy, she contributed to the electoral victory of the alliance between the PSA and Patrice Lumumba’s Congolese National Movement (MNC).

Impressed by her conviction and organizational talent, Lumumba appointed her head of protocol and entrusted her with writing several official speeches. Behind the scenes, she became his adviser and political ally. The people soon called her “the woman behind Lumumba.”

But her rise was abruptly cut short. After Lumumba’s assassination in January 1961, Andrée Blouin was expelled from Congo. A long exile began. From Algeria to Switzerland, she continued to fight for African unity, women’s rights, and social justice.

In her autobiography My Country, Africa: Autobiography of the Black Pasionaria, she tells a rare and moving story: a woman who, against all odds (racism, sexism, exclusion) chose to fight for a continent’s emancipation.

Andrée Blouin died in Paris on April 9, 1986, far from her native Africa. But her voice, her words, and her flame continue to transcend time like a breath of freedom.

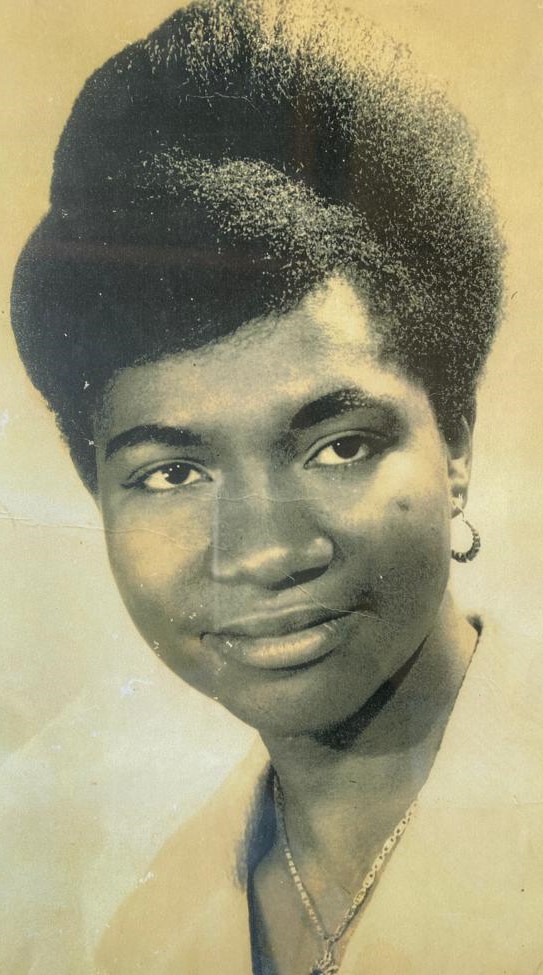

Joséphine Swale Maya Kapongo: Early MNC Activist

A nurse aide by profession, Joséphine Swale joined the Congolese National Movement/Lumumba (MNC/L) when it was founded on October 5, 1958. She committed herself fervently alongside major figures such as Patrice Lumumba, Cyrille Adoula, and Joseph Ileo. In this fledgling party, dominated by men in the political bureau, Joséphine Swale distinguished herself through intelligence, loyalty, and unwavering commitment. She was one of the few women to hold a strategic position behind the scenes, discreet but essential.

Yet, like many women activists of the time, she was often overshadowed by her male counterparts in historical accounts. Nevertheless, her contribution to the political awakening of Congo’s population remains significant.

Marie Kanza: The Loyal Shadow of the Resistance

In the shadow of the illustrious figures of her family (Sophie Kanza, the first female minister of the DRC, and Thomas Kanza, the first Congolese academic graduate from Belgium), Marie Kanza carved out a path all her own: discreet but essential.

The first Black Congolese nurse in the Belgian Congo, Marie Kanza combined care with subversion. According to the document The Founding Mothers: Pioneering for Africa’s Independence, she played a strategic role in the underground networks of the independence struggle, acting as an intelligence agent during the tense years preceding independence. Her ally? A French lawyer based in France, committed to the Congolese cause. Marie Kanza served as a link between Kinshasa and Brazzaville, hiding subscription money in her clothes, crossing the river, risking arrest at every passage. She carried funds, messages, hope, silently, with quiet determination.

Her commitment, invisible to the colonial press and often omitted from official accounts, was nevertheless decisive in supporting legal and political efforts led from abroad. Even today, her name remains less known than those of her illustrious relatives. Yet without women like her, the march toward independence might have faltered.

Julienne Mbengi: The Voice of Bakongo Women in the Colonial Storm

At a time when women were kept away from political arenas, Julienne Mbengi founded an autonomous space for speech and action. In 1958, amid nationalist ferment, she created FABAKO (Women of the Alliance of the Bakongo), a women’s organization linked to ABAKO, the powerful political and cultural movement of Bas-Congo, led by Joseph Kasa-Vubu, future president of the Republic.

FABAKO aimed to be a relay for Bakongo women’s demands, a mobilization space in neighborhoods, markets, and churches, places where the destiny of a people was also being forged.

However, despite its ideological ties to ABAKO, FABAKO was never recognized as an official branch of the party. This marginalization revealed persistent tensions between male spheres of power and autonomous women’s initiatives. As often, the women’s struggle had to unfold in parallel, on the margins of the official narrative.

Louise Efoli: The Sharp Pen of La Voix du Congolais

In 1956, in a Congo still under colonial domination, Louise Efoli wrote the second article ever published by a woman in La Voix du Congolais, a prestigious periodical founded by the colonial administration but gradually becoming a platform for so-called “evolved” Congolese intellectuals.

But Louise Efoli also challenged these same “evolved” men, those who proclaimed their modernity, thirst for freedom, and rejection of colonial yoke, while perpetuating condescending attitudes and discourse toward women. In a lucid and bold text, she denounced the contradictions of these male elites, who advocated emancipation but denied Congolese women an autonomous voice.

The Ten Forgotten Heroines: A Clandestine Women’s Front for Peace and Recognition

In the shadow of the great men of African independence, a group of ten Congolese women rose up, united by a common fight: peace and recognition of Congo on the African stage. The Founding Mothers: Pioneering for Africa’s Independence reveals their little-known but essential story.

Coming from various political movements and associations, often in disagreement, these women managed to overcome their differences to mobilize together. In the aftermath of independence, when the country was torn by civil war and rebellion under Tshombé’s regime, they undertook a bold journey: meeting Kwame Nkrumah, president of Ghana, where several Congolese rebels had found refuge after the tragic assassination of Patrice Lumumba.

Their message was simple and poignant: “Do not support the rebellion, our children are dying on the front.” This plea moved Nkrumah, who granted them his support. But their fight did not stop there. In 1964, when Congo was excluded from the Organization of African Unity (OAU) conference, they took the lead once again. This collective, composed of Marie Thérèse Ilondo, Anna Kembe, Joséphine Maya Kapongo, Antoinette Kidawaza, Anne Mukanda, Marie Jeanne Feza, Véronique Kani, Emily Ekwekele, Marie Ofela, and Victorine Njoli, traveled to Egypt to plead the Congolese cause.

To strengthen their position, they staged a hunger strike, a powerful symbolic act that drew the attention of delegates and the media. Their determination paid off: the Congolese delegation was finally admitted among the OAU members, a crucial step toward international recognition and restoring their country’s dignity.

These women, often absent from history books, are silent pioneers. Their courage and solidarity helped lay the first stones of an engaged women’s diplomacy, carrying hope and reconciliation in a troubled political context.

Véronique Kani would become the first female mayor of the city of Kinshasa. She was appointed mayor of the Bandalungwa commune.

At just 21 years old, Victorine “Vicky” Njoli Lokenga became the first Congolese woman to obtain a driver’s license, on January 25, 1955, at the driver training school in Leopoldville, present-day Kinshasa. She earned her license with high distinction, passing all tests brilliantly, and also became the first Congolese woman to drive a car, a strong symbol of emancipation and independence.

At the same time, Victorine Njoli showed remarkable entrepreneurial spirit by launching a successful sewing business, combining modernity and tradition. Her career brilliantly illustrates the role of pioneering women who, through their boldness and successes, opened the way to new freedoms for future generations.