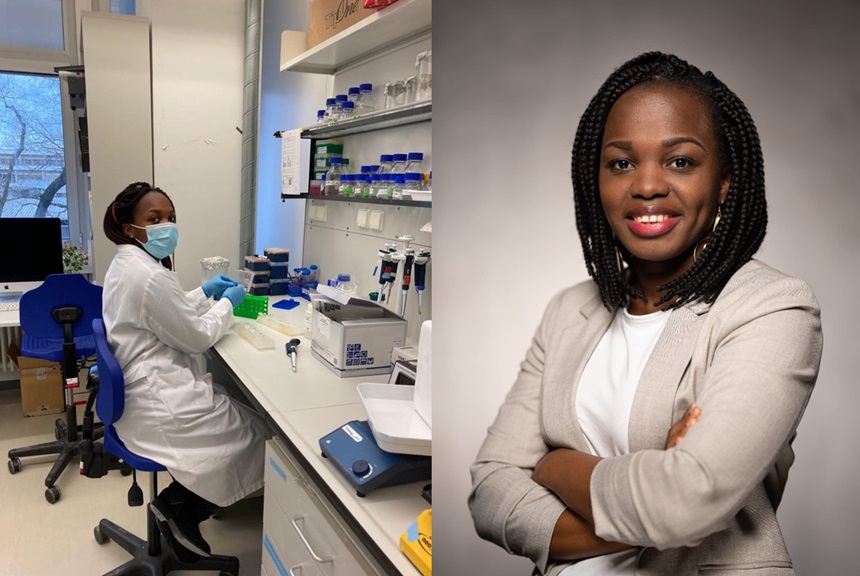

Originally from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Tania Bishola Tshitenge,32, trained as a molecular biologist, is currently a research scientist with the German multinational Bayer, which operates in the pharmaceutical and agrochemical sectors. She is also an associate professor at the University of Kinshasa, co-founder of the Academy of Sciences for Young People in the DRC (ASJ-RDC), and founder and president of the Zoe-Liziba Foundation, an NGO that works through orphanages to help improve the living conditions of orphaned and vulnerable children.

Where does your interest in molecular biology come from?

My interest in molecular biology stems from my curiosity to understand the cause of different infectious and parasitic diseases at a molecular level. I was very curious to acquire knowledge about the different transmission routes of infectious agents, the biochemical and molecular pathways involved in their invasion of the host cell and the means that could be used to prevent (vaccines) and combat infection (drugs). I was very passionate about understanding the mechanisms of action of drugs and vaccines at the molecular and cellular levels.

How did you get to where you are today?

I did my primary and secondary education (biology and chemistry option) at the “Joyeux-Lutins” school complex and the “Lycée Motema Mpiko” in Kinshasa, DRC, respectively. I wanted to study medicine at university, but financial problems prevented me from starting the academic year at the Protestant University of Congo on time. I told myself that the Lord was directing my steps towards biology, which subsequently captivated all my attention and fascinated my whole life. So I started studying biology at the University of Kinshasa with the aim of transferring to medicine. But after my first year, I was so passionate about the content of the field that I decided not to transfer to medicine and to continue my studies in biology, with molecular biology as an option. In 2013, during my final year, I did a three-month placement in Ghana, at the Noguchi Medical Research Institute, where I learnt some molecular biology methods, such as PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction), agarose electrophoresis and sequencing.

After my undergraduate studies, which were heavily supported by the Bringmann Excellence Scholarship to Congolese Universities (BEBUC), I won a scholarship from the German Research Foundation (DFG) to do a Masters in Biotechnology at the University of Nairobi, Kenya, alternating with Germany. My Masters research was conducted at the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (ICIPE) in Kenya, where I worked on olfactory receptors in the tsetse fly.

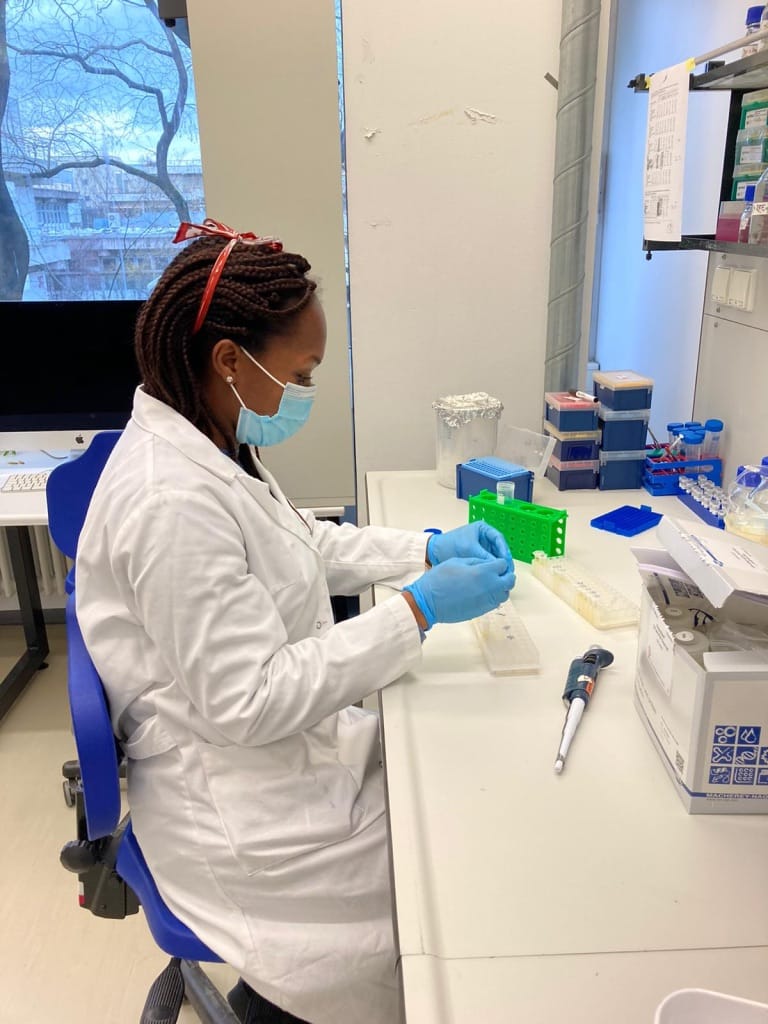

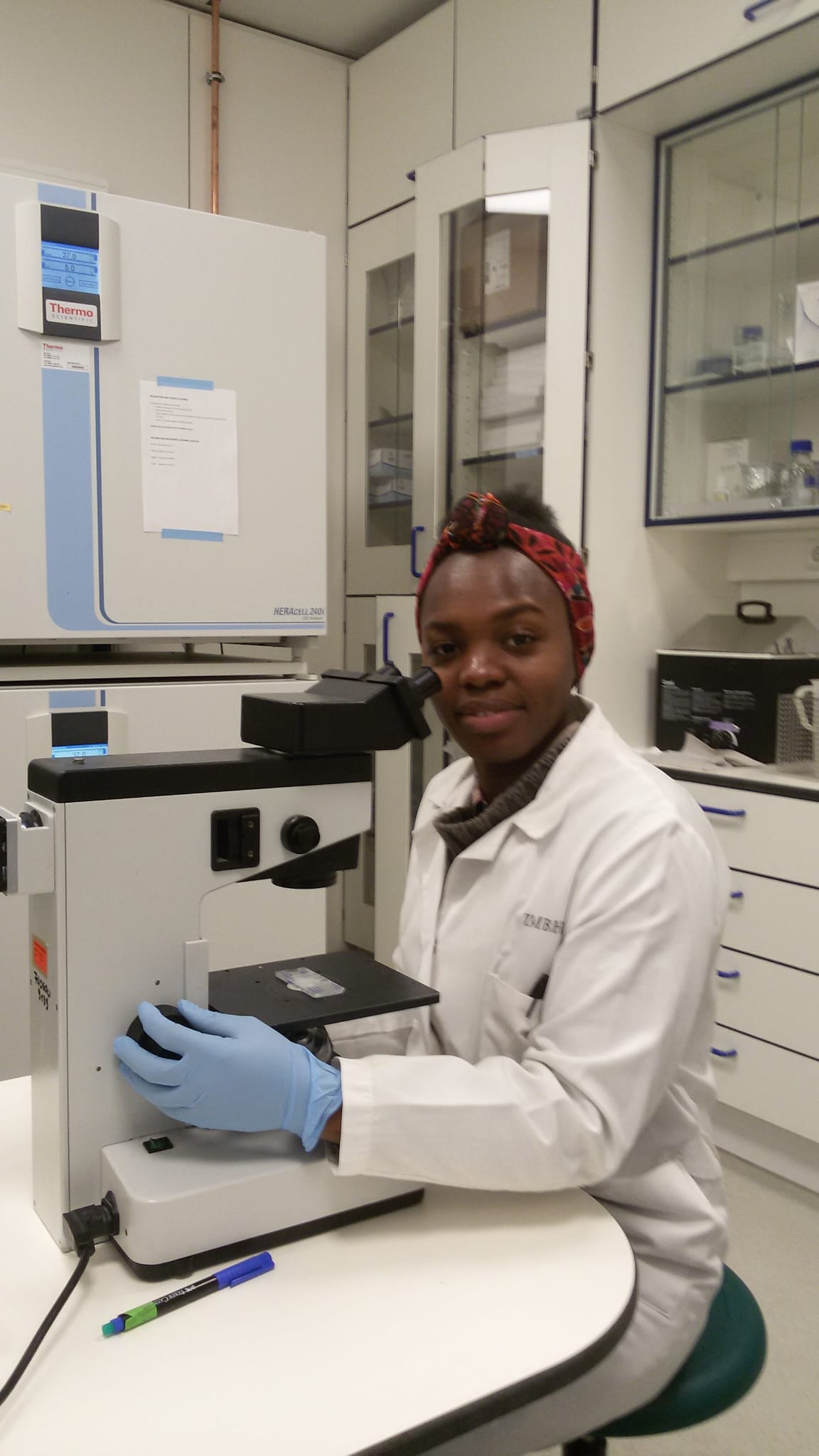

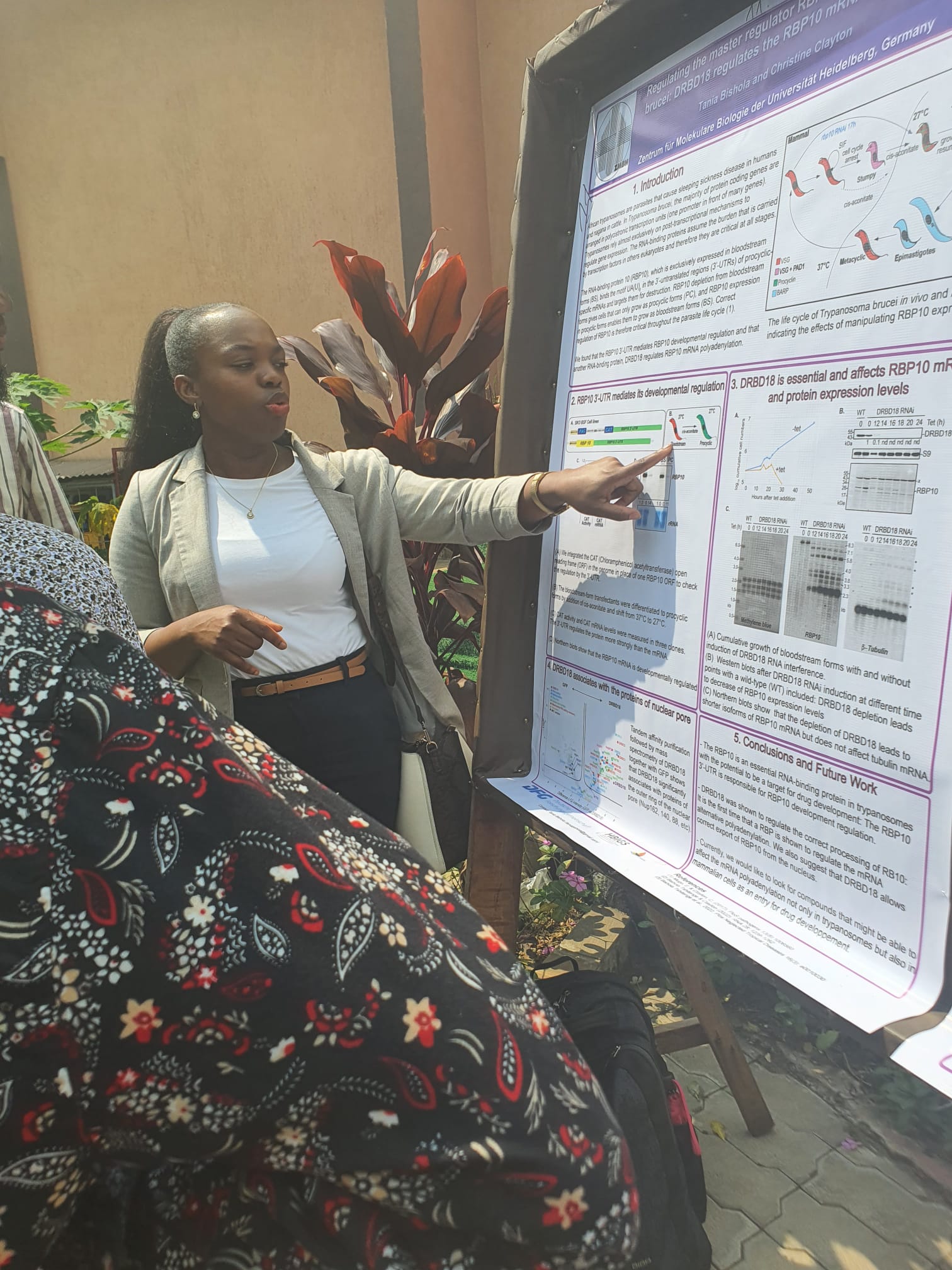

After brilliantly defending my Master’s thesis in 2017 in Nairobi, I was then selected by the University of Heidelberg’s doctoral programme in life sciences (HBIGS). I was awarded a scholarship to do my PhD in Professor Christine Clayton’s laboratory. The laboratory was part of the Centre for Molecular Biology at the University of Heidelberg (ZMBH) in Germany. I therefore spent 4 years of hard work (2017-2021) researching the regulation of gene expression, using the trypanosome parasite as a model system. It was during these years that I developed a passion for RNA biology and realised that it would offer huge opportunities for vaccines and medicines in the future. During this period, I took part in several international conferences, where I presented the results of my research and won prizes for excellence.

After my doctoral studies, i returned to the DRC to apply for the position of associate professor. This was granted at the end of 2022. I started teaching molecular biology and genetic engineering at the University of Kinshasa in January 2023.

Since May 2022, I’ve been doing postdoctoral studies at the Bayer pharmaceutical company, where I’m developing new approaches to transcriptomics to understand how drugs act at the RNA level.

What is your speciality?

My speciality is molecular biology, and more specifically I’m passionate about RNA biology. The subjects I specialize in are the regulation of gene expression, which I have mastered a great deal using the trypanosome as a model system. I’m also very involved in new transcriptomics approaches to understanding the modes of action of drugs (and chemicals) and in the DRC, my research revolves around the biological activities of natural compounds from medicinal plants to combat disease.

What does your current research involve at Bayer? What is your objective?

My research projects at Bayer focus on the development of new sequencing approaches (NGS, next generation sequencing) for chemical transcriptomics on an industrial scale in order to understand the modes of action of drugs at the RNA level. Using standard and novel transcriptomics approaches, I support company projects involved in oncology, nephrology, gene therapy to understand targets of action and drug development. I also work on research projects aimed at targeting RNA with chemical molecules for the development of new therapies for cancer and other diseases.

How important is this research for a country like the DRC?

For a country like the DRC, which has been weakened by decades of war and armed conflict, and which faces recurring epidemics, there is an ongoing need to develop innovative approaches to vaccines and medicines to combat and prevent the infectious diseases that ravage the country. The knowledge acquired in the field of RNA is therefore extremely important for the development of future vaccines and medicines. For some diseases, it is still difficult to target the proteins of the pathogen, and RNA offers us new opportunities in the fight against these diseases.

You are one of the ten winners of the “Women in Africa (WIA) Young Leaders 2023” initiative and the first Congolese to take part. What does this programme involve and what are your expectations?

The WIA Young Leaders programme is one of the initiatives of the Women in Africa organisation, which aims to support and highlight young African women leaders who will play a major role in the African revolution and who are destined to become emblematic players in Africa’s economic growth. This year marks the third edition of this programme, developed in partnership with the Dior brand, the French investment bank Lazard, Africa’s leading digital player Huawei North Africa, the audit and consultancy firm KPMG France and the global multi-energy company TotalEnergies.

This year, 10 of us leaders benefited from a tailor-made training programme focusing on female leadership and the skills of tomorrow. During a week-long trip to Paris in October, we took part in several international events, which gave us access to a high-level professional network, training on key issues such as governance, the opportunity to meet experts in different sectors and high visibility. Throughout 2024, we will continue to receive these various training courses and will also benefit from special mentoring to help us develop our professional careers.

What advances do you hope to see in your field of research in the future?

We hope to find new avenues of gene therapy for certain incurable diseases, and that we can also demonstrate that RNA offers a target pathway for the development of drugs and vaccines.

What research or discoveries have made the biggest impact on you in recent years in Africa in general, and in the DRC in particular?

The discoveries that have impressed me most are the research carried out in Africa in collaboration with the West, which has led to the development of malaria vaccines. These vaccines were recently approved by the WHO and are currently being administered in more than 12 African countries. These vaccines truly represent a major advance in the fight against malaria, a highly fatal disease in Africa, especially for children under the age of 5.

In the DRC, I am very impressed by the work that Professor Hyppolite Mavoko, from the Faculty of Medicine at the University of Kinshasa, and his team are doing to conduct clinical trials of an Ebola vaccine in the remote rainforests of the DRC. This also represents an enormous advance in research, especially as it would improve preparedness for Ebola epidemics in the DRC. And we believe that the effectiveness of the vaccine would reduce the possibility of contracting the virus in the future.

What courses do you teach at the University of Kinshasa?

I teach genetic engineering and molecular biology to second-year biology students in the Faculty of Science at the University of Kinshasa.

The genetic engineering course focuses on the basics of molecular biology (DNA and RNA structure, gene organisation, and gene expression processes such as transcription and translation); the different techniques and tools of molecular biology and the methodologies used in gene manipulation, such as DNA and RNA extraction, PCR, agarose gel electrophoresis, cloning and sequencing. The course also includes a section on the applications of genetic engineering in biotechnology (genetically modified organisms such as transgenic plants, animals and insects) and in the medical field (development of RNA vaccines, production of insulin, gene therapy through gene editing, etc.).

The Molecular Biology Elements course is based on detailed notions of molecular biology, including the structure of DNA and RNA, gene organisation, the processes of gene expression, such as DNA replication, transcription of DNA into RNA and translation of RNA into proteins and the mechanisms that are used by the organism to regulate gene expression. We also give a brief introduction to the techniques and methods used to analyse nucleic acids, such as PCR, electrophoresis and sequencing.

What would you like your students to remember?

By teaching these courses, my main aim is to enable students to acquire important knowledge about molecular biology and to understand the role that this discipline currently plays in several areas of research, whether in the detection of infectious diseases (PCR tests, etc.), in their prevention (development of vaccines) or in their treatment (development of drugs), or in crop improvement (transgenic plants), and in the eradication of diseases (transgenic mosquitoes in Brazil to eradicate the Zika virus), and so on.

Why did you co-found the science academy for young people in the DRC?

My friends and I were motivated by the desire to fill a gap that existed in our country. Every country has a science academy for young researchers, and these academies are affiliated to the World Academy of Young Scientists (https://globalyoungacademy.net/ ). We believe that this academy will be a platform for promoting interaction between young scientists from different disciplines with a view to tackling the national and international challenges facing our society. It is for this reason that we co-founded the Academy of Sciences for Young People in the DRC (ASJ-RDC). As its motto states, “science at the service of society”, the ASJ-RDC places particular emphasis on the relationship between the scientific world and the development of society.

What are its aims and objectives?

Its aims are to enable young Congolese scientists to play an active part in identifying the needs of their communities, drawing up policies to meet those needs and implementing those policies through concrete action, in collaboration with the stakeholders concerned; to promote science as a career of choice for young Congolese, by serving as a role model and an example to follow, and by taking action to remove obstacles linked to gender, tribes or ethnic groups; to strengthen the capacity for scientific research in the DRC, by establishing science as a driving force for economic development and participating in exchange programmes between scientists from both national and international institutions; to encourage the development of innovative approaches to solving problems of national and international importance, in collaboration with the global network of national youth academies in various countries and the World Youth Academy; to attract the interest of the government, research foundations and other philanthropic organizations in investing in research projects.

What activities are carried out?

The main activities include international conferences and plenary sessions at the country’s universities to promote science, discuss the various branches of science, inform the scientific community of new scientific advances and discoveries and encourage students to choose science as a career; science days organised in schools throughout the country, during which we give laboratory demonstrations, arouse pupils’ curiosity about scientific subjects, try to demystify science and demonstrate the usefulness of science in dealing with society’s problems; prize-giving ceremonies for the best students in certain faculties at some of the country’s universities; appearances by members of the Academy on programmes organised by certain television channels to inform society about the usefulness of science and new scientific advances; the participation of members of the Academy in international conferences organised by the science academies of other African countries and those organised by the World Academy of Young Scientists; the selection of full members of the Academy, which is carried out annually following a call for nominations and evaluation by an international committee made up of members of the science academies of other African countries.

What are the advantages and disadvantages of being a woman in science?

I don’t know if there is any advantage in itself that is specific to a woman in science. One advantage that I have observed is that there are currently a number of organisations and grants that have been set up to support women in science in particular. These include programmes such as l’Oréal-Unesco for Women in Science, the Schlumberger Foundation and the Organisation for Women in Science in the Developing World (OWSD), to name but a few. Another advantage is that, for most science-related fellowships and funds, there is currently a desire to give particular preference to female applicants, since they are rare. So this becomes an advantage.

I also think that science and research require precision, dedication, passion and above all patience, which are qualities that women naturally possess. So they have an advantage and they always produce something exceptional in the scientific field.

The first disadvantage is that the scientific fields have historically been much more male-dominated for a long time, and this has created a serious taboo for women scientists and technologists, who are very stereotyped. In some societies, science is seen as a more male-dominated field.

There are even prejudices such as girls not being good at maths or not being suited to engineering. This explains the low representation of women in the sciences, particularly STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics), the inequality of their salaries compared to their male colleagues and their low access to positions of great responsibility as leaders of institutions or universities.

Another long-standing problem is that, according to one analysis, women who contribute to scientific research are under-represented in publications compared to their male colleagues. They are less likely to be cited as authors in articles or as inventors in patents than their male colleagues, even though they do the same amount of work. This is partly because women’s contributions to research are “often unrecognized, unappreciated or ignored”, say some of the authors.

Another concern for women in science is the work-life balance. Housewives have more responsibility for domestic chores. Pregnancy, maternity leave and breast-feeding can easily be a hindrance or obstacle to their professional growth and development, compared with their male colleagues.

There are very few female scientific figures in the media in Africa and the DRC. What could be the reason for this?

First of all, it’s linked to the low representation of women in the scientific field. In Africa, according to a UNESCO report, only 30% of researchers are women and, in STEM fields, they are often paid less and publish less. Often, most of them do not progress as far in their careers as their male counterparts, because of the various challenges they face. Also, as I’ve already mentioned, one of the challenges facing women scientists is that they don’t very often benefit from the spin-offs of their discoveries, the prestige of their work often going to their male colleagues, and this reduces their media exposure as they are therefore forgotten and minimised.

For those who do emerge in the scientific field, either they haven’t had enough media opportunities to highlight their research or some of them are also very shy and don’t like to be highlighted by the media.

Who is your role model in the scientific field?

I have several role models in the scientific field, but I’ll mention just three here: Professor Christine Clayton, who was the supervisor of my doctoral thesis, and Professor Nina Papavasiliou, who was the co-supervisor of my doctoral thesis. Both of them not only mentored me, but also introduced me to critical thinking, precision, excellence and delicacy in scientific research. They are an example to me of passion for research, excellence, perseverance and patience. Another role model for me is Francine Ntoumi from the Congo, who never ceases to inspire me with the quality of her scientific research, her courage, her perseverance despite all the challenges in Africa, her collaborative spirit and her exciting leadership.

What are your goals for the next few years?

I have many goals for the coming years. But the most important are to set up a biochemistry and molecular biology laboratory at the University of Kinshasa, which will enable me to start my own research in the field of RNA biology applied to infectious diseases, build up my work team and train the next generation of scientific researchers.

Within the academy of sciences for young people in the DRC, we would like to organise international conferences over the next few years, to which members of other academies in African countries will be invited, as well as young Congolese scientists in the diaspora. Together with the academies of young scientists in other African countries, we are developing an academy for young scientists in Africa. We believe that this platform will increase interaction between young African researchers and enable them to discuss major problems common to African society.

As part of my Fondation Zoe-Liziba, over the next few years we plan to set up a training center and/or school for vulnerable children, enabling them to acquire knowledge that will enable them to be useful to society.