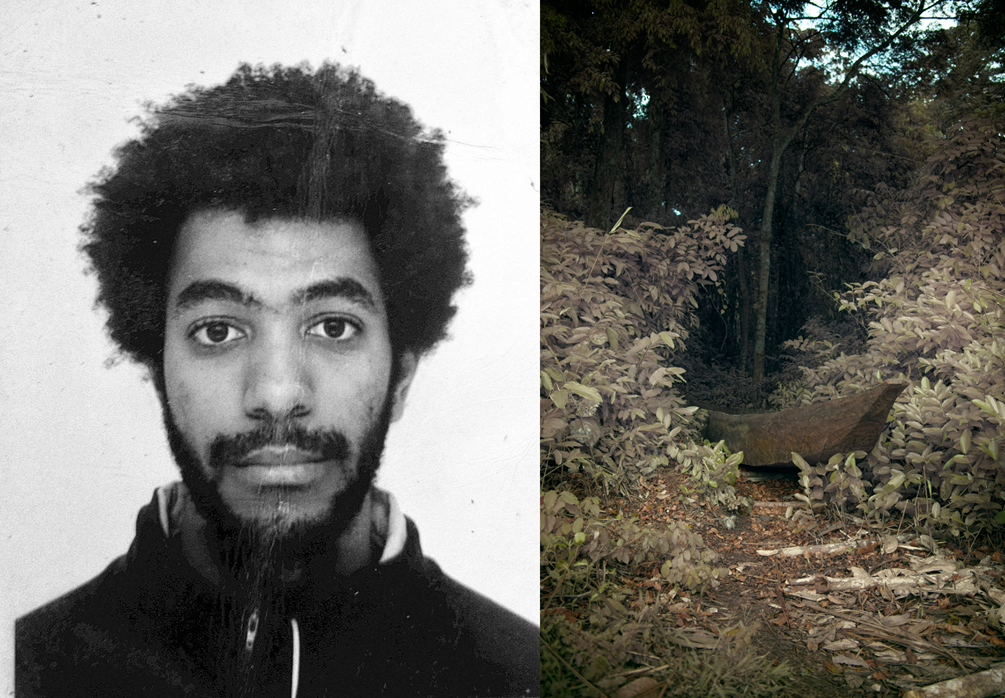

Léonard Pongo is a Belgian-Congolese visual artist and photography teacher at the Kinshasa Academy of Fine Arts, as well as a film director. His first monograph, “The Uncanny”, was recently published by Gostbooks, an independent publishing house specializing in visual arts and photography, based in London. The Uncanny is a photographic project carried out between 2011 and 2017 in the urban centers of Congo.

Africanshapers: How long have you been working as a visual artist?

I’ve been teaching at the Académie des Beaux-Arts since the photo department opened three years ago. But I had already been giving workshops since 2018, in collaboration with the Goethe Institute in Kinshasa. I also taught photography in Malaysia, from 2014 to 2018.

How did you move from Belgium to Malaysia?

Very early on, I didn’t want to limit my work to the Belgian environment. I found places and partners to show my work outside Belgium. I got into the habit of communicating in English, following my studies in political science, so that I could be in contact with a wide audience. I had sent work to Malaysia that I had started in Kinshasa in 2011 and continued afterwards in several cities in the Congo. I sent it to festivals and organizations. As a result, I was selected for several festivals, which helped me build up a network. During a festival in Cambodia, the director of another festival in Malaysia saw my work, liked my approach and asked me to teach. He was collaborating with Australia, so Australian students came too, as well as students from all over Malaysia. Every summer, for 5 years, I was invited to teach in Malaysia. I was mainly involved in artistic accompaniment, guiding young photographers in the development of their projects.

How does one go from political science to visual artist?

It’s a long-term job of “corruption” on the part of my father, who is an architect (Laughs). From a very early age, he trained us in storytelling, because he’d had storyteller friends come over since we were little. We grew up with this culture of listening to stories being told to us and an African culture always shared. In addition, every week my father would give us a space to draw. It was a very free drawing class, with no obligations. The aim was simply to draw. I went on to study political science. But I realized that I was missing something: the ability to express myself visually and not just to write scientific essays. That’s when I got back into the visual arts through photography. I taught myself how to use the camera. At the same time, I was working as a graphic designer for my student association. This also sharpened my eye. In 2009, I took a photography course in Brussels, and in 2010, I started working as a freelancer for a Brussels newspaper.

You’ve just published your first monograph, “The Uncanny”. What is the content of this book?

The Uncanny is a term derived from Freudian psychoanalysis. It’s the idea of the strangely familiar. To be in a familiar place, which you recognize, but for things not to be the way you expect them to be, like, for example, something not being in the right place or not being the right color. It was very much connected to my own experience. Being in the Congo, a place I knew only through my family members. For many young people from the diaspora, even if we grow up in a given country, our cultural and identity reference is the Congo, a country we only know via the adults around us or the information we can consult from outside. I wanted to express this feeling of being in a familiar environment, but sometimes very different from what I imagined. This shock had an impact on me because I was transformed when I reconnected with my roots. It was also a way of taking readers into an experience of this complex space. I wanted to include the audience in something very personal, while at the same time sending out a polysemous message about the complex reality of the DRC.

What themes does the book address?

The book deals with a number of themes. In addition to the experience of a complex space, the book deals with a journey through many of the realities that can be found in the Congo and that make up the daily life of the Congolese people. I produced the book by following the daily lives of members of my family and also by working with television crews who report daily news. There’s this mix between news that isn’t “interesting” for the international scene but which, on a national level, reflects the daily life of the Congolese people. These are realities I wanted to connect with. So it was important for me to highlight these elements. Apart from the photos, the book contains a very short text, written by Nadia Yala Kisukidi, a philosophy professor in Paris.

Was it easy for people to accept being photographed or published in a book?

Often, in the Western world, there is this relationship with the image. I’ve often been told that in Kinshasa I’d never be able to take photos, that I’d have problems and conflicts. That hasn’t been the case for me. People express themselves on whether or not they agree to be photographed. They question you. It hasn’t always been comfortable for me, but it’s helped me connect. If you’re holding a camera, people ask you why you’re taking pictures. It’s just a way of making the connection and the contact. And, very often, people didn’t want to be photographed. That wasn’t a problem for me. My aim wasn’t to take pictures of a specific person, but rather to experience the atmosphere of a space and communicate it. For example, I took pictures in a bar called “Les branchés”, which no longer exists. It took me a month to regularly visit the young people there. When the images were taken, I also gave them to them. In the end, it was they who asked me to take their photos. 12 years later, it’s a pleasure to be able to look at all these photographic archives. The fact that a person refuses to be photographed is not a limitation.

How many photos does the book contain?

The book contains 111 images. Which is a lot for a book dedicated to photography. These images were taken between 2011 and 2018. I made a selection, as I took almost 70,000 photos for this project.

Why did you wait so long to publish the book?

In the world of photography, it’s usually the photographers who pay for their book to be published. I refused this procedure from the start, because it’s too expensive. I researched for several years and was able to get a grant in 2020 that enabled me to publish this book. I don’t have to pay the publisher, because the publishing house covers the costs. If the books are sold, I don’t make any personal profit, but it allows me to have my book on the market and to be able to distribute my photos. So it was thanks to this grant that I was able to publish “The Uncanny”. From 2020 onwards, it took me another two years of work to really put the book together, including the choice of the final images to be published.

Some of your photographs are currently on show at the Tate Museum in London. Which works are they?

It’s a new project I’ve been working on since 2017 called “Primordial Earth”. The basis of the project is a questioning of the earth. I grew up with the idea that our identity comes from the land where we live, and that we’re a bit like a piece of our territory. I wanted to question how we can enter into a dialogue with our land. It’s a love letter to the Congolese land and our traditions. I really wanted to understand and also to fit into a traditional line of thought. The main question was how I could represent the Congolese landscape in a traditional way. To do this, I questioned elderly people, traditional chiefs and my own family. I also visited key sites in the Congo with strong symbolism, notably Monkoto. I tried to find places that resonated a little with the places described in the traditions, or elements and shapes that often appear.

So the aim of this exhibition is to try and recreate a space where we can experience the power and beauty of our land.

Where did you visit in the Congo?

I visited some key sites in the Congo, with very strong symbolic value, notably Monkoto, Kananga, Katanga and Kivu. I went to my family’s village “Mukengele” in the Kasai, in the Dibaya territory. I went to Kananga, where I spoke with Chief Kalamba. I asked him where he thought I should go to represent our land. I also travelled along the Luluwa River. I went to Monkoto, in Equateur province; to Garamba park; to Virunga national park; to Central Kongo. I also climbed to the summit of Nyiragongo, where I spent a few nights with a team of scientists. At the end of last year, I spent a month and a half in the Upemba National Park (Katanga).

Are all these trips self-financed?

I’ve been working as a photojournalist for 10 years, and I use my commissions to get to certain places. I’ve also benefited from the support of Upemba Park and its director, Tina Lain, as well as several creative support grants and awards for my work, which have enabled me to continue my projects.

Is the “Primordial Earth” exhibition also being shown in the Congo?

Yes. Already, as I’m a teacher in Congo, I organize sessions with students at the Academy of Fine Arts about the films I’ve worked on or my exhibitions. Also last year, in August, I presented my work at the first Photography Encounters at the Academy of Fine Arts. The “Primordial Earth” photo project was shown for the first time in Bamako, in 2019. The following month, the photo project was also shown at the Lubumbashi Biennale. Now I’m looking for a venue to show the exhibition in Kinshasa. Nevertheless, the short film (Primordial Earth: inhabiting the landscape) has already been shown at the 2022 edition of the Lubumbashi biennale.

On this subject, you’re currently making a film, due for release soon…

Indeed, this experimental film will be released next year and is entitled “Tales from the Source”. It lasts 39 minutes and I spent 2 years making it. It’s still part of the drive to show the Congolese landscape as a source of knowledge for mankind.

It also aims to present a vision of the land inspired by the symbolism and traditions that stem from our identities. The Congo is home to over 400 ethnic groups, and that’s an enormous wealth. It’s about questioning whether the sources are in the earth and whether we can dialogue with the landscape. Will the landscape respond to me? Can I find symbolic forms in our traditional arts, which are often described as primitive art, as if they were less important than Western art. For me, traditional art is complex and embodies philosophies. These are people who have lived for generations and built up their own knowledge and that of their environment. So there’s a great richness there. I borrow this idea from the Senegalese philosopher Souleymane Bachir Diagne, who wrote a book on the subject entitled “African Art as Philosophy”. That’s what prompted me to ask myself questions about the subject, and to explore it from the DRC’s point of view, using video. The film will be shown at the next Lubumbashi Biennial.

What other films have you already made?

The Necessary Evil, which I made between 2011 and 2013 in revivalist churches in Kinshasa; “Primordial Earth”, made in 2020, proposes a reading of life on earth with the Congo as the source of everything, the alpha and omega of life on the planet. Then there’s “Tales of the Source”, due out next year.

What are your plans?

For next year, I’d like to distribute the film by finding the right platforms to show it. I’d also like to present it in the Congo. Two multimedia installations are already planned in Marrakech for February 2024, not just for the film, but for all my artistic work. I’m also planning to take part in the Dakar biennial, a key event for contemporary art on the continent, which will take place in May, and also in the Lubumbashi biennial.